Air quality management systems in the United Kingdom invite public participation only after pollution problems have already been identified and defined—a fundamental flaw that limits community input to commentary rather than meaningful involvement in decisions that affect their health. Research published in Communications Earth & Environment argues that creating truly participatory air quality governance requires rebuilding the institutional structures that determine whose knowledge counts and when.

The Current System's Limitations

Under the UK's Environment Act of 1995, local councils received delegated authority to monitor and mitigate air quality through stationary equipment that tracks legal thresholds of predetermined pollutants. When measurements exceed established limits, authorities designate the affected area as an Air Quality Management Area and produce an accompanying Air Quality Action Plan. Only at this stage can public consultation begin.

According to researchers Karl Dudman, Kayla Schulte, and Ruaraidh Dobson, this framework inherently limits public participation by excluding communities from earlier, more consequential decisions. By the time consultation occurs, authorities have already determined how poor air quality is defined (based on specific pollutant concentrations), what constitutes representative exposure (based on data from stationary monitors in technician-selected locations), and who is authorized to initiate remedial action (local authorities).

The compliance-based framework reduces air quality to a binary classification of "good" and "bad" air, overlooking harms from chronic low-level exposure and missing opportunities for public involvement in preventative action before legal limits are breached.

The Concept of Knowledge Infrastructure

The researchers introduce the concept of "knowledge infrastructure"—the processes controlling who decides what, when, and how information is used to manage air quality. While technological infrastructure such as monitoring equipment and software undergoes ongoing innovation to avoid obsolescence, knowledge infrastructure determining which actors and inputs are considered legitimate has remained largely unchanged.

Social research consistently demonstrates that residents hold important environmental expertise as experts in their own lives and communities and as the beneficiaries of problem-solving whose understanding matters. Despite this evidence, the UK's air quality management framework confines public participation to a commentary role, invited only after the fundamental parameters have been established.

The researchers argue that aspirations for deeper participation require overhauling existing knowledge infrastructure to allow public partners to help define what the problem is, what causes it, how severe it is, and how it might be addressed.

Government-Level Innovation: Ella's Law

At the national government level, technological infrastructure for air quality management receives regular updates through working groups that draw on scientific evidence to inform policy. The Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollution, for example, has been consulted to inform reductions in legal pollution limits. Regulatory standards such as the Monitoring Certification Scheme ensure consistent monitoring practices.

The researchers suggest that parallel mechanisms should exist for updating knowledge infrastructure as societal expectations of participation evolve. One promising example is the proposed creation of a Citizens' Commission for Clean Air under the Clean Air (Human Rights) Bill, commonly called "Ella's Law."

Named for Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, the first person in the UK whose death was officially linked to air pollution, the bill currently under development in the House of Commons would legally mandate the right to clean air. Among its provisions, the Citizens' Commission for Clean Air would involve and represent members of the public, assessing the adequacy of government action and advising the secretary of state on improvements to reporting.

While the bill remains in development, the Commission represents a protected institutional platform at the national government level where public input in air quality management could be overseen and safeguarded by community representatives themselves.

Academic Research Contributions

Academic expertise regularly feeds into air quality decision-making through commissioned research and solicitation of evidence for special projects or technology assessments. In air quality science, research has overwhelmingly focused on technical updates improving measurement accuracy, reducing spatiotemporal granularity, and linking pollution data with health impacts.

The researchers note that extending existing channels for academic consultation could complement technical expertise with insights from social sciences and humanities. A sophisticated canon of research already exists comparing models for embedding diverse knowledge into decision-making processes, identifying obstacles to meaningful participation, and distinguishing between authentic and superficial methods of engaging publics.

Incorporating this existing expertise represents a straightforward approach to updating air quality's knowledge infrastructure without requiring entirely new institutional mechanisms.

Subnational Experiments and Innovation

Innovations at the subnational level have played increasingly significant roles in air quality management's technological infrastructure. Rapid advancements in low-cost sensors have made pollution monitoring more mobile, affordable, and scalable. These predominantly private-sector innovations have become integrated within government strategies and now represent fundamental parts of the governance ecosystem.

The researchers suggest that similar subnational activities could influence participatory management practices. They highlight the competency group model developed in Pickering, North Yorkshire, where community members and hydrologists collaborated to share, scrutinize, and synthesize insights about local flood risks. Subsequent flood mitigation efforts gained broad public legitimacy from incorporating local expertise and established a model for collaboration between social and scientific knowledge.

The Breathe London Communities initiative represents another example, involving researchers, businesses, local government, and residents in collaborative efforts where community members use low-cost sensors to measure air quality in locations they identify as concerning. With this data, residents can advocate for local improvements based on their own place-based expertise.

According to the researchers, these experiments demonstrate that technological advances can serve either as instruments of public empowerment or exclusion, depending on deployment approaches. Emerging interpretations of the UN Aarhus Convention identify possible regulatory pathways for mandating inclusion of citizen-generated environmental data throughout government decision-making.

Moving Beyond Symbolic Participation

The research emphasizes that public participation in air quality management cannot simply be appended to existing outdated systems. Despite growing interest in participatory approaches, UK regulations structurally lack capacity for meaningful public input—a legacy from times when "relevant knowledge" referred exclusively to scientific expertise.

The researchers argue this necessitates updating air quality management's knowledge infrastructure by redefining which forms of expertise and evidence are considered policy-relevant and how they are used in governance. By adapting existing channels for innovating air quality management in government, academia, and nonstate contexts, future interventions can ensure that engagement with social and place-based experiences of polluted air becomes structurally embedded rather than merely symbolic.

Indoor Air Quality and Personal Action

While systemic changes to air quality governance unfold slowly through policy development and institutional reform, individuals can take immediate action to protect their families from air pollution exposure. According to EPA estimates, Americans spend approximately 90% of their time indoors, making residential air quality a critical component of total exposure.

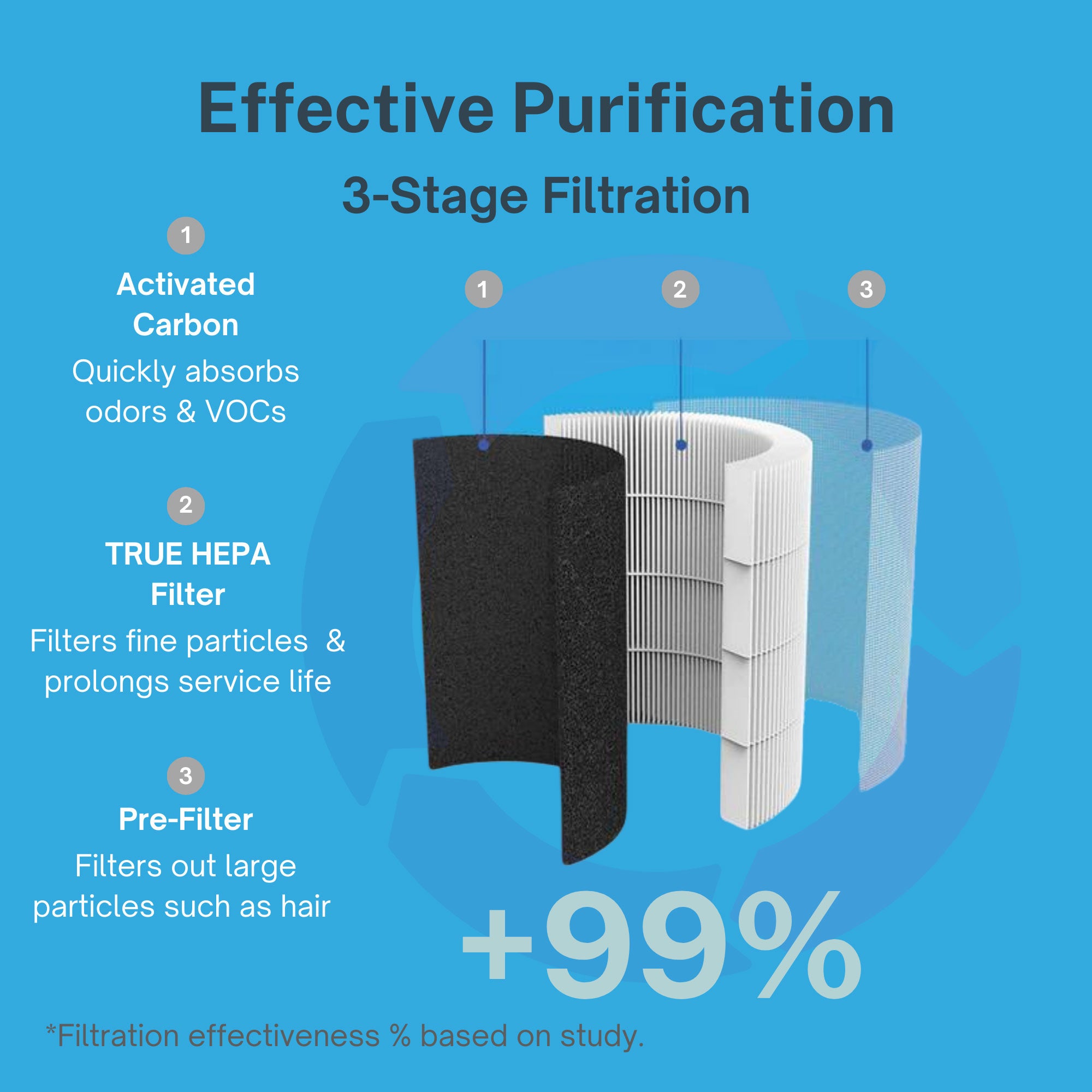

The iAdaptAir system provides medical-grade HEPA filtration that captures 99.97% of particles as small as 0.3 microns, effectively removing the fine particulate matter that represents one of the most significant health threats from air pollution. Combined with activated carbon filtration for gaseous pollutants and UV-C technology for biological contaminants, comprehensive indoor air purification addresses multiple pollution types simultaneously.

For families concerned about outdoor air quality—whether from traffic emissions, industrial sources, or seasonal events like wildfires—maintaining clean indoor air provides practical protection while broader governance reforms develop.

Create Healthier Indoor Environments

Air quality governance systems are beginning to recognize the importance of community knowledge and participation in decision-making, but structural changes occur gradually. While you cannot control outdoor pollution sources or speed institutional reform, you can take immediate action to protect your family's indoor air quality.

Invest in scientifically validated air purification technology that removes harmful pollutants from your home environment. Shop Air Oasis today and create cleaner indoor air for your family regardless of outdoor conditions or governance challenges.